Meeting Xiomara Vidal at the Casa De La Trova

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

After my first night in Hostel Girasol, I set off in search of a guitar teacher who can guide me through the labyrinth of Cuban rhythms and genres.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

I had just finished reading a book on the plane called ‘Looking For La Bomba: The Cuban Misadventures of a Musical Oaf’, by Richard Neill. It tells the story of a man who ditches his job to pursue his ambition to play bass for a Cuban son band.

Throughout the book, he toils trying to find la bomba or ‘the bomb’. This is the expression Cubans use to describe that innate, affecting musicality that some souls are gifted with.

This book is the perfect companion to my mission in Cuba, and the setting is right here in Santiago de Cuba. I gather from the author that the Casa de la Trova, the cradle of the trova style, is the epicentre of the Santiago music scene.

So my first stop will be there.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”494″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_separator color=”green”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Trovadors & their Trova” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Lobster%3Aregular|font_style:400%20regular%3A400%3Anormal”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”1193″ img_size=”150×210″ alignment=”center” css_animation=”bottom-to-top”][vc_custom_heading text=”‘A trovador is a poet with a guitar’ – Silvio Rodriguez” font_container=”tag:h1|font_size:18|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Lobster%3Aregular|font_style:400%20regular%3A400%3Anormal” css=”.vc_custom_1596057791581{margin-top: -15px !important;}”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1592918951999{border-radius: 1px !important;}”][vc_column_text]

trobar “to find, invent, compose in verse”

trou•ba•dour ‘A medieval lyric poet composing and singing in southern France, eastern Spain, and northern Italy in the early 11th-13th centuries.’

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]The concept of the travelling musician is surely as old as the invention of instruments and songs themselves, however, the term troubadour originates in 11th century feudal Europe where these early characters emerged. Troubadours were travelling musicians who would sing of courtly love, publicise events and recount fabulous stories of other cultures over their musical compositions.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row top_margin=”0″ bottom_margin=”0″ el_id=”pepe-sanchez”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As stringed instruments were further developed in successive centuries, the guitar would emerge as the weapon of choice. Its portability and capacity to create a fuller solo accompaniment were qualities that lent themselves to the demands of the travelling musician.

Eventually, this term would find its way from medieval Europe, via colonialism, to 19th century Cuba. Here, musicians toured through villages and towns offering their trova songs, employing various genres to achieve the desired effect. It was in Santiago de Cuba and Sancti Spiritus where these travelling musicians flourished with the greatest abundance and began to be known by the name trovador.

The beginning of the 20th century is seen as the ‘golden age’ of the trova cubana. This was an era spearheaded by Pepe Sánchez and his contemporaries.[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”green”][vc_custom_heading text=”Pepe Sánchez” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Lobster%3Aregular|font_style:400%20regular%3A400%3Anormal”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Pepe Sánchez is honoured with the titles: ‘Father of the trova’ and ‘Father of the Cuban bolero’. His song Tristezas (Sorrows) was written in 1883 and is touted as the first known instance of this style.

He was born in Santiago de Cuba on 19th March 1856 and originally worked as a tailor.

Unlike the more formal composers of his generation, he was a self-taught guitarist who composed using the ideas in his head and his guitar. As such, few of his compositions were transcribed but a rich oral tradition has helped preserve them to this day.

As well as being a guitarist and trovador, he also developed an active role as a cultural promoter forming mixed choirs, composing for theatre and directing orchestras.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”642″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_border” onclick=”link_image”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

In addition to his most famous boleros, Tristeza and Cristinita, he composed many other boleros, canciones, criollas and guarachas.

He died in obscurity on 3rd January 1918 but in 1962, following the Cuban Revolution, the National Festival of the Trova was established bearing his name. It closes on March 19, his birthday, now named National Day of the Trova.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Source: Lino Betancourt & Eduardo Ramos. ‘Como La Rosa, Como el Perfume’. Ediciones Museo de la Música, 2011. Havana.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:13|text_align:justify|color:%23000000″ use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_empty_space][vc_separator color=”green”][vc_custom_heading text=”Casa de la Trova” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Lobster%3Aregular|font_style:400%20regular%3A400%3Anormal”][vc_custom_heading text=”Meeting Xiomara Vidal” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Lobster%3Aregular|font_style:400%20regular%3A400%3Anormal” css=”.vc_custom_1592924144110{margin-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column_text]

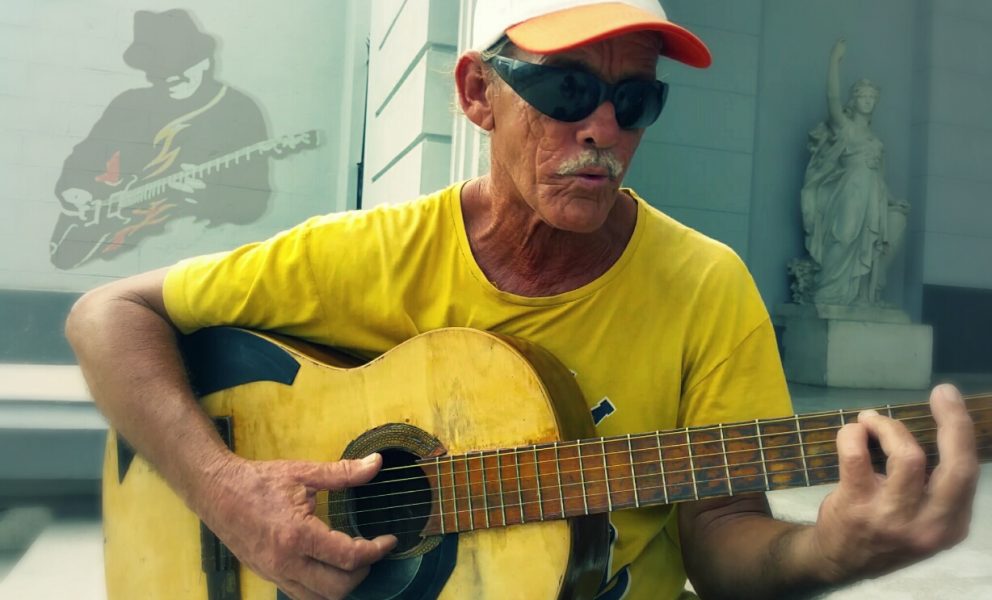

As I walk down Calle Heredia, I hear the infectious vibes of a live son band, the heavy syncopation willing the hips and legs to do… something. My salsa moves are non-existent so I stoically resist. As I get closer I realise that the music is coming from the Casa de la Trova.

There is a room on the corner of the building’s ground floor with three large openings onto the pavement, with bars restricting access to the room itself. A pack of hangers-on are pressed against them watching the group warm up.

Further along, next to the main room is a smaller, cosier room. This is the original Casa de la Trova (or Trovita as it is affectionately known) which also has one wall largely open to the street.

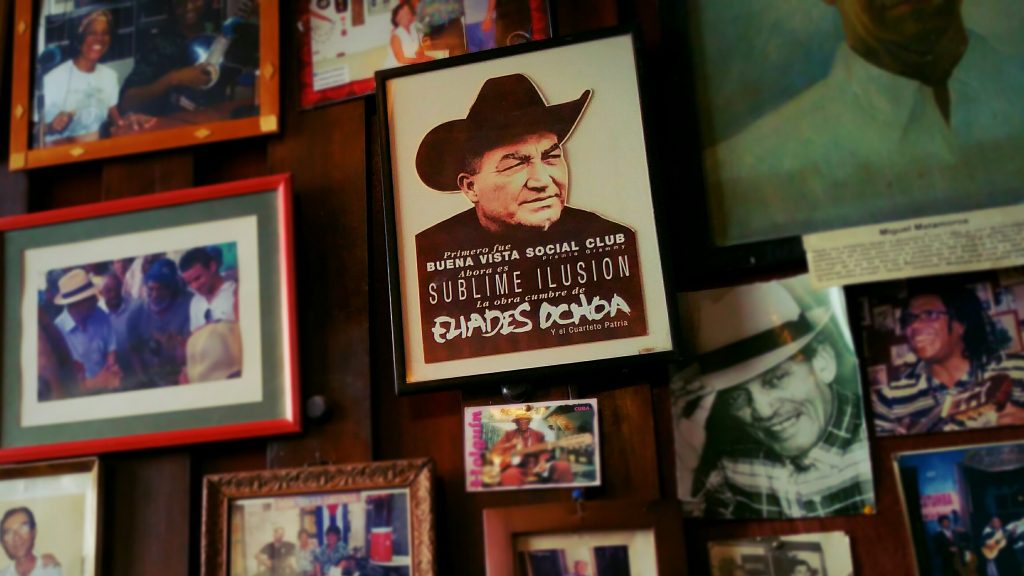

Peering in, I see the walls jam-packed with framed pictures of Santiago’s musical giants. As I ogle them, a lady who is selling souvenirs at the front rouses me and we strike up a conversation. I ask if she knows of any guitar teachers who play at the Casa de la Trova. She smiles and points towards the back of the room where there is a charismatic lady sitting on the edge of the stage with a guitar.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″ animation=”right-to-left”][vc_column_text]

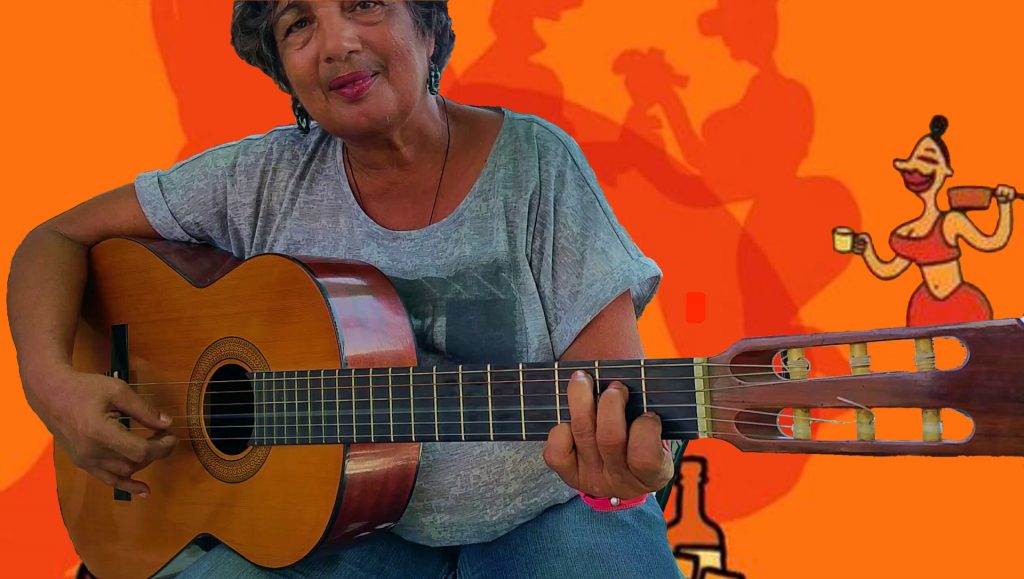

I stroll on over with my guitar slung over my shoulder, introduce myself and explain that I am looking for someone who can teach me traditional Cuban music.

She is intrigued by my story and describes her background. She describes herself as a nueva trovadora, performing twice a week here at the Casa de la Trova, as well at the Casa del Queso on the opposite corner.

She performs a mixture of the classic traditional Cuban repertoire with a more modern nueva trova (‘new trova’) spin, as well as her own boleros numbering more than 50.

I tell her I’d be very interested in learning some of her nueva trova songs as well as the traditional styles. I can see from her expression that she is pleased I’m showing an interest in these, as well as the long tradition from which they span.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”645″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_border” onclick=”link_image”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

But first things first. She invites me to take a seat so that she can play me some songs. She unsheathes her large-body classical guitar, takes command of the stage and confidently belts out a set. Her voice soars across the Casa and out into the street. She’s supported by two backing singers, who lock in with emotive harmonies, whilst playing clave and maracas.

During her performance, I am propositioned by a vivacious Cuban salsa dancer. I try to sweet talk my way out of this sticky situation but she insists on a little less conversation, and a little more action. Without further ado, she whips me up out of my chair for an impromptu lesson. My inner Mr. Bean makes another cameo appearance. As I am whirled around, awkwardly, I notice Xiomara smirking through the corner of her mouth. How very dare you.

After Xiomara’s set, she asks me to play her a song. I play her the finger-style Beatles number ‘Blackbird’, and although nobody seems to understand the English lyrics, I sense that the sweet harmony and overall sentiment resonate with them. But then that’s the beauty of music: it’s a universal language.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”497″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_border” onclick=”link_image”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_images_carousel images=”498″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

Xiomara then smiles and gestures for me to follow her. I think she’s got a surprise for me…

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]